Larry Summers

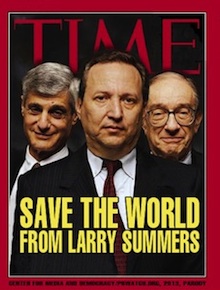

Lawrence Henry "Larry" Summers was a primary architect of the modern U.S. financial system, which collapsed in 2008 leaving some 8 million Americans unemployed and destroying some $13 trillion in wealth, according to the GAO. Summers served multiple roles in the U.S. Treasury in the 1990's under President Clinton and Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin (previously of Goldman-Sachs). In those roles he supported the repeal of Glass-Steagall, which lead to the creation of "too big to fail" banks, and fought the regulation of derivatives which later played a key role in the financial crisis (see more below). Ultimately he became Secretary of the Treasury under Clinton 1999-2001. He also held the position as President of Harvard 2001-2006 during the administration of George W. Bush, a position he left after a no-confidence vote by the staff and after losing some $2 billion in Harvard endowment funds to a derivatives deal gone bad.[1] He would later become the Director of President Obama's National Economic Council, an economic policy agency within the executive branch of the U.S. government from 2008-2010, and play a key role in bailing out the U.S. banking system.[2] In 2013, he is a top candidate for the position of Federal Reserve Chairman.

Contents

- 1 Role in financial crisis and bailout

- 2 Record and controversies

- 2.1 Role as Director of the National Economic Council

- 2.2 Links to the Financial Industry

- 2.3 Views on the Role of Regulation in Financial Markets

- 2.4 Views on the Role of the Finance Industry in the US Economy

- 2.5 Views on Trade

- 2.6 Views on Social Programs

- 2.7 Role in the Enron Crisis

- 2.8 Role in International Crises

- 2.9 Harvard

- 3 Tobacco

- 4 Background info

- 5 Contact details

- 6 Articles & resources

Role in financial crisis and bailout

Documents Related to Summers' Efforts to Deregulate U.S. Derivatives Markets

The final report of the National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in the United States puts over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives "at the center of the storm," and specifically cites the Commodities Futures Modernization Act as a major contributing factor. "The enactment of legislation in 2000 to ban the regulation by both the federal and state governments of over-the-counter derivatives was a key turning point in the march towards the financial crisis." Read the report, pg. xxiv, here.[4]

In the spring of 1998, Deputy Treasury Secretary Larry Summers called Brooksley Born, the head of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), and yelled: "I have 13 bankers in my office who tell me you're going to cause the worst financial crisis since the end of World War II" if she moved forward with plans to bring transparency and reporting requirements to the OTC market. OTC derivatives were already causing huge loses around the globe. In 1994 Orange County California lost $1.5 billion speculating on OTC derivatives. Watch the Frontline investigation "The Warning" here.[5]

Summers attacked Born publicly, testifying in Congress in July 1998: "As you know, Mr. Chairman, the CFTC's recent concept release has been a matter of serious concern, not merely to Treasury but to all those with an interest in the OTC derivatives market. In our view, the Release has cast the shadow of regulatory uncertainty over an otherwise thriving market -- raising risks for the stability and competitiveness of American derivative trading. We believe it is quite important that the doubts be eliminated." "The parties to these kinds of contracts are largely sophisticated financial institutions that would appear to be eminently capable of protecting themselves from fraud and counterparty insolvencies." Read Summers testimony here.[6]

One of Summers primary arguments was that any new regulation could invalidate the burgeoning swaps market, yet Born made it clear in her release and in her testimony that new rules would be prospective. Previously the CFTC had generated prospective rules. "The release does not in any way alter the current status of any instrument or transaction under the Commodity Exchange Act. Any proposed regulatory modifications resulting from the concept release would be subject to rulemaking procedures, including public comment, and any changes that imposed new regulatory obligations or restrictions would be applied prospectively only." Read the concept release here.[7]

Even though the 1998 Long-Term Capital Management derivatives disaster shook regulators and demonstrated that derivatives deals could pose systemic risk to the entire economy, bank regulators and Congress ignored Born who cited "an immediate and pressing need to address possible regulatory protections in the OTC derivatives market." Instead they placed a six month moratorium on any CFTC regulation and Born resigned in early 1999. Read Born's speech on LTCM here.[8]

Summers became Treasury Secretary in July 1999, receiving a congratulatory letter from Ken Lay, the President of Enron Corporation, addressed "Dear Larry." In his response to "Ken" on May 25, 1999, Summers included a handwritten PS: "I'll keep my eye on power deregulation and energy-market infrastructure issues." Read the letters here.[9]

Summers helped negotiate the World Trade Organization's Financial Services agreement that opened global markets to derivatives and other financial products and made it harder for signatory nations to regulate banking in the public interest. In the WTO agreement, which was negotiated behind closed doors, the United States effectively pledged to get rid of the 1933 Glass-Steagall law, which was seen as a barrier to market entry by many foreign banks that were structured differently.[10] In 1997, Tim Geither urged Larry Summers to personally call the heads of America's top five banks to seal the deal. See the Geithner memo to Summers here.[11]

Summers pushed for the repeal of the Glass-Steagall, which was created after the Great Depression to wall off traditional commercial banking activity from the Wall Street casino. The repeal allowed commercial banks to merge with investment banks, securities firms and insurance companies, creating "too big to fail" behemoths and unleashing an era of reckless speculation. On November 5, 1999 Summers hailed the passage of the repeal: "Today Congress voted to update the rules that have governed financial services since the Great Depression and replace them with a system for the 21st Century. This historic legislation will better enable American companies to compete in the new economy." Read the statement here.[12]

On November 9, 1999, Summers and other regulators issued a report that would serve as the Congressional blueprint for the Commodities Futures Modernization Act drafted the following year. The "President's Working Group on Financial Markets" concluded that "under many circumstances, the trading of financial derivatives by eligible swap participants should be excluded from the CEA [Commodities Exchange Act]. To do otherwise would perpetuate legal uncertainty or impose unnecessary regulatory burdens and constraints upon the development of these markets in the United States." Read the Working Group Report here.[13]

Summers personally reassured Ken Lay on November 22, 1999 that Enron's derivatives trades would not be regulated, directing him to pages 34-35 in the Working Group report that reads "in light of their small market share and the apparent effectiveness of private counterparty discipline in constraining the risk-taking of such derivatives dealers, the Working Group is not recommending legislative action with respect to such derivatives dealers at this time." Read the letter here.[14]

Summers wrote to Congress on December 15, 2000 to "strongly support" the Commodities Futures Modernization Act. The bill that went even further than the legal changes called for in the President's Working Group Report, exempting derivatives from regulation by any federal bank regulator not just the CFTC. Summers also allowed the "Enron Loophole" to be included in bill (over the objections of the CFTC), which exempted energy trading on electronic commodity markets from regulation and helped Enron to gouge billions of dollars from West Coast consumers. Read the letter in the Congressional Record here.[15]

As energy prices skyrocketed in California, Summers opposed Governor Gray Davis' plan to intervene with price controls, claiming: "This is classic supply and demand. The only way to fix this is ultimately by allowing retail prices to go wherever they have to go." Enron filed for bankruptcy in 2001, putting 20,000 employees out of work and Ken Lay was convicted of 10 counts of securities fraud, wire fraud and other offenses. Read Kurt Eichenwald's 2005 book on the collapse of Enron, "Conspiracy of Fools."[16]

Summers departed the Treasury in 2001 and went off to be the President of Harvard, where he ignored repeated warnings by expert staff and lost Harvard some $2 billion of its endowment funds, including $1 billion on toxic interest rate swaps. Read about it in the Boston Globe[17] and Bloomberg.[18]

Back at the White House in 2009 as head of the National Economic Council, Summers was a chief architect of the generous bank bailout, the weak stimulus and the limited structural reforms in Dodd-Frank. Summers opposed numerous efforts to strengthen the bill, most tellingly, the President's effort to include the "Volcker Rule." Volcker's aim was to put an end some of the riskiest practices by curtailing proprietary trading at U.S. banks and limiting their investments in private equity firms and hedge funds, but the rule was slow walked and weakened by Summers. Read Richard Wolffe's book "Revival: The Struggle for Survival Inside the Obama White House."[19]

Summers was overheard in November of 2008 chastising Arthur Levitt (former head of the SEC under Clinton) for saying that Brooksley Born was right "I read somewhere you were saying that maybe Brooksley Born was right. ... But you know she was really wrong." Levitt confirmed the account, available here.[20]

In the years that followed the 2008 meltdown, Clinton, Greenspan, Levitt even Rubin admitted they made mistakes or expressed some regret for these actions. Summers abided by his own advice to Geithner, as Geithner prepped for his confirmation session as Treasury Secretary, "don't anyone admit we did anything wrong." Read Ron Suskind's "Confidence Men."

In 2012, Summers was grilled by a British reporter and defended his record on derivatives, saying "at the time Bill Clinton was president, there essentially were no credit default swaps. So the issue that became a serious problem really wasn't an issue that was on the horizon... If you want to assign responsibility, If you take a market that essentially didn't exist in the 1990s, that grew for eight years from 2001 to 2008, and then brought on a major collapse, if you were looking to hold people responsible, you would look to... officials of the Bush Administration." Credit default swaps were invented by JP Morgan Chase to offset the risk of the Exxon Valdez disaster in 1994 and plenty of people were worried about them, including presidential adviser Joseph Stiglitz.[21] Watch the Summers interview here.[22]

According to the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission's final report in the shadows, between 2000-2008, the OTC derivatives market grew from $95.2 trillion to $672.6 trillion (Report pg. 48 here.) notational value.[4] When the dark market deals started to go sour, the impact was felt around the world.

Advocate of Financial Deregulation

Between 1992 and 2001, Summers held various positions in the US Treasury Department, including that of Treasury Secretary from 1999 to 2001.[23] Summers has described the 1990’s as a time when “important steps” were taken to achieve “deregulation in key sectors of the economy” such as financial services. He has also said that during this period government officials and private financial interests collaborated in a spirit of cooperation “to provide the right framework for our financial industry to thrive.” [24] Summers recommended before he left the Treasury Department that removing policies that “artificially constrict the size of markets” should remain a priority for the US government.[25]

Along with Robert Rubin and Alan Greenspan, Summers brought about elimination of key US financial regulations including the Glass-Steagall Act. He was particularly aggressive in his efforts to block regulations of derivatives, regulations that might have prevented the economic meltdown the US suffered in 2008. According to economist Dean Baker, "The policies he promoted as Treasury Secretary and in his subsequent writings led to the economic disaster that we now face." [26]

Support for Repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act

When he was Treasury Secretary, Larry Summers advocated repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act[27], which was a target of the financial industry. In their report - “Sold Out: How Wall Street and Washington Betrayed America” - Robert Weissman and Harry Rosenfeld identified the repeal of this legislation as one of the main causes of the 2008 financial crisis. According to Weissman and Rosenfeld, “The Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999 formally repealed the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 (also known as the Banking Act of 1933) and related laws, which prohibited commercial banks from offering investment banking and insurance services…The 1999 repeal of Glass-Steagall helped create the conditions in which banks invested monies from checking and savings accounts into creative financial instruments such as mortgage-backed securities and credit default swaps, investment gambles that rocked the financial markets in 2008.” [28]

Summers worked for Congressional approval of the Financial Services Modernization Act, sponsored by Republicans Phil Gramm, Jim Leach and Thomas Bliley. This Act eliminated provisions in the Glass-Steagall Act that prohibited banks from affiliating with securities firms. It also repealed provisions in the Bank Holding Company Act that prevented banks from underwriting insurance. Arianna Huffington points out that the Financial Services Modernization Act “created an oversight disaster, with supervision of banking conglomerates split among a host of different government agencies -- agencies that often failed to let each other know what they were doing and what they were uncovering.” [29]

Summers has promoted financial deregulation as a form of modernization, rather than a return to the lack of government oversight and instability of the pre-Depression era. In 1999, Summers claimed the Financial Services Modernization Act would create a financial regulatory system “for the 21st century” and “promote stability in our financial system.” [30] However, Democrat Senator Byron Dorgan warned at the time “I think we will look back in 10 years’ time and say we should not have done this, but we did because we forgot the lessons of the past, and that that which is true in the 1930s is true in 2010. We have now decided in the name of modernization to forget the lessons of the past, of safety and of soundness.” [31]

Summers argued for elimination of the Glass-Steagall Act by saying it imposed “archaic financial restrictions.”[32] He said that the US government “must allow competition to work” and that meant “allowing common ownership of banking, securities and insurance firms.” Summers insisted that US financial organizations must have the ability to choose “the structure that is right for them” and to offer “a full range of products.” In Summers’ view, the Financial Services Modernization Act that repealed Glass-Steagall struck the right balance between giving financial institutions more flexibility and protecting US taxpayers. [33]

Summers cast the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act as a victory for the international competitiveness of US financial firms and for US consumers: “If it can be done without compromising other critical objectives, repeal of the common ownership restrictions of current law would be an important boost to our financial system. Our leadership of the world's financial markets would be enhanced. And consumers would see the benefits in the form of greater innovation and lower prices.” [34]

However, the financial innovation that followed the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act has been criticized for its damaging effects on the US economy and US taxpayers. In their report proposing financial regulatory reform, the Congressional Oversight Panel for the Troubled Asset Relief Program observed that “Creativity and innovation are too often channeled into circumventing regulation and exploiting loopholes.” The Panel’s report notes how after the introduction of key financial regulations during the Depression - including the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act that Summers helped to repeal - the US had enjoyed a long period of high economic growth that was also free of major financial crises. [35]

Opposition to Regulation of Derivatives

Summers’ principal link to the 2008 financial crisis may be the role he played while at the Treasury Department in blocking regulation of derivatives [36]. Conducted outside of formal exchanges, most derivative trading is not only unregulated, it is also largely unreported so that the full extent of the risk financial institutions are exposed to cannot be known. Over-the-counter derivatives are traded in “dark markets” with little transparency.

Summers argued as Treasury Secretary that the US should deregulate derivative markets so they could grow. He saw benefits for the US housing market from expansion of derivatives, arguing that “by enabling more sophisticated management of assets, including mortgages, consumer loans, and corporate debt, derivatives can help lower mortgage payments, insurance premiums, and other financing costs for American consumers and businesses.” [37]

However, Frank Partnoy, a former Wall Street trader, has explained how unregulated derivatives transformed the US sub-prime mortgage crisis into a full-blown global financial crisis. “Without derivatives, the total losses from the spike in subprime mortgage defaults would have been relatively small and easily contained…Instead, derivatives multiplied the losses from subprime mortgage loans, through side bets based on credit default swaps [38]. Still more credit default swaps, based on defaults by banks and insurance companies themselves, magnified losses on the subprime side bets. As investors learned about all of this side betting, they began to lose confidence in the system. When they looked at the banks’ financial statements, all they saw were vague and incomplete references to unregulated derivatives.”[39]

While he was at the Treasury Department, Summers’ enthusiasm for financial deregulation conflicted with the views of Brooksley Born, who became Chair of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission in 1996. Born had extensive previous experience working as a lawyer in the derivatives area and was concerned about the lack of oversight of this multi-trillion dollar financial market. However, Summers collaborated with Alan Greenspan, Robert Rubin, and Arthur Levitt to block Born’s efforts to initiate discussion of regulating derivatives. According to New York Times report Timothy O’Brien “They were all part of a very concerted effort to shut her up and to shut her down. And they did, in fact, shut her up and shut her down. Bob Rubin is not a guy who likes confrontation. He's confrontation-averse. But he understands that you need someone in there who can swing a heavy axe, and that person was Larry Summers. He was the enforcer.” [40]

Former CFTC director Michael Greenberger has recounted how Summers called Born personally to accuse her of risking a major financial crisis with her proposal [41] to discuss regulation of derivatives. Summers echoed the concerns of bankers who were in his office at the time he made the call to Born.[42]

In his Senate Committee testimony opposing Brooksley Born’s initiative, Summers stated that opening the door to regulation of derivatives had “cast the shadow of regulatory uncertainty over an otherwise thriving market - raising risks for the stability and competitiveness of American derivative trading.” Summers opposed even raising “the possibility of increased regulation over this market” because of the uncertainty it might create. [43]

Summers praised the $26 trillion, unregulated, over-the-counter (OTC) US derivatives market as “second to none”, playing “a major role in our own economy”, and acting as “a magnet for derivative business from around the world”. Summers argued that not only Wall Street but also the average person had an interest in the growth of derivatives markets: “OTC derivatives directly and indirectly support higher investment and growth in living standards in the United States and around the world.”.[44]

Summers’ view of derivatives as benefiting average Americans contrasted with Born’s, who testified that "Losses resulting from misuse of OTC derivatives instruments or from sales practice abuses in the OTC derivatives market can affect many Americans." [45] The US economy had already experienced a number of disasters that signaled the dangers of unregulated derivatives: the largest municipal bankruptcy in US history – that of Orange County, California – occurred in 1994 because of losses on derivatives amounting to $1000 for every resident[46]; two US corporations – Proctor and Gamble and Gibson’s Greeting Cards – had been “taken to the cleaners” in 1994 by derivative traders from Bankers Trust[47]; and in 1998, as Summers was testifying about the risk-management benefits of derivatives, Long Term Capital Management was in the process of self-destructing and almost taking the banking system down with it, having made $1.25 trillion in derivative trades with major banks despite holding only $4 billion to back them up. [48]

Support for Permanent Deregulation of Derivatives

As well as blocking Brooksley Born’s efforts to regulate derivatives, Summers worked to ensure derivatives remained permanently deregulated by promoting passage of the Commodity Futures Modernization Act. [49] Summers said the Act would “allow the United States to maintain its competitive position in this rapidly growing sector…” This legislation was another piece of deregulatory legislation sponsored by Republican Senator Phil Gramm. Summers supported the Act’s exclusion of over-the-counter derivatives from regulation under the Commodity Exchange Act, and also from state-level laws that regulate gambling.

In a report [50] he co-authored on derivatives that preceded passage of the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, Summers recommended the US government permanently exclude from the Commodity Exchange Act derivative trades between “sophisticated” parties. While Summers was President of Harvard, the university purchased derivatives in the form of interest rate swap contracts. These derivative contracts involved Harvard in paying high fee to investment banks and having to compensate for massive losses when interest rates fell. The losses occurred despite the “sophistication” in financial issues that might have been expected of Harvard’s leaders, including Summers. [51]

Summers and his co-authors in the report on derivatives argued against imposing “unnecessary regulatory burdens and constraints upon the development of these markets in the United States.” Although the US had already experienced problems with derivatives, the report concluded there was “no compelling evidence of problems involving bilateral swap agreements that would warrant regulation under the Commodity Exchange Act.” [52]

Summers characterized both the Financial Services Modernization Act and the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, despite their deregulatory impacts, as “clear steps to strengthen the integrity of America's financial system.” He told a business lobby group that “Even in the U.S., with the most open financial markets in the world, further deregulation of domestic financial markets, as we've recognized in our financial services legislation proposals, can make an important difference in spurring a healthier and more efficient financial sector.”[53]

Record and controversies

Role as Director of the National Economic Council

The National Economic Council is the agency responsible for advising the U.S. President on economic policy. As Director of the NEC, Summers is “the only top adviser with a West Wing office, sees the president more than the other economic advisers and controls the daily economic briefings.” [54]

Summers had a key role in determining the size of the economic stimulus package the Obama administration submitted to Congress. In a July 2009 speech, Summers highlighted how bad the economy was when the Obama administration took office. He said “Fear was widespread and confidence was scarce.” The lesson he took from previous economic crises was that government’s response could not be “too little or too late.” [55]

The size of the stimulus however has been criticized as too little. Economist Paul Krugman warned that while cutting the size of the stimulus might get more Republican votes, it would fail to significantly reduce unemployment. This failure would then be blamed on the Democrats and be used to argue that government spending does not work. [56]

Links to the Financial Industry

After resigning under pressure from being President of Harvard University, Summers sought jobs on Wall Street with Goldman Sachs and Citigroup. [57] He was hired by one of the world’s largest hedge funds, D.E. Shaw, where he worked one day a week and earned $5.2 million in the year before he became Director of the National Economic Council. [58] Between 2004 and 2006, he had worked as a consultant for another hedge fund, Taconic Capital Advisors. In 2009, Summers tried to get one of the founders of Taconic appointed to head the government’s financial bailout oversight office. Summers now seeks input on public policy issues from the hedge fund managers he met while working with the industry, including the CEO of BlackRock. [59]

While his former financial industry colleagues say they feel more confident in the administration with Summers in his current post, others have questioned whether the public is served by his ties to the financial sector. Professor Andrew Sabl has said “This is what might be called contamination. Did Summers spend so much time with the hedge fund, or its investors, sovereign wealth funds, and so on, that he started to think like them?” [60]

Summers’ financial disclosure forms for 2008 indicate that in addition to his $5.2 million compensation from D.E. Shaw, he also earned $2.7 million in speaking fees. Among the financial institutions that paid him to speak were JP Morgan Chase, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, Lehman Brothers and Merrill Lynch, with Goldman Sachs paying $135,000 for a single appearance. [61]

Views on the Role of Regulation in Financial Markets

As Treasury Secretary, Summers recognized potential problems could arise due to “lack of transparency, the risks that hedging strategies and models may not live up to their design, and the toxic combination of excessive leverage and illiquidity.” These problems would end up creating the 2008 financial crisis. However, despite his own criticisms of the notion that markets are self-correcting, in 2000 Summers argued against government regulation on the grounds that the financial industry had demonstrated “significant self-correction where excesses had developed”. He gave the following rationale for limited government oversight of the financial industry:

“As I have stated before, it is the private sector, not the public sector, that is in the best position to provide effective supervision and reduce the likelihood that these issues rise to a level that could threaten market stability. Market discipline is the first line of defense in maintaining the integrity of our financial system.”

The “best approach to regulation” in Summers’ view, was “to ensure that public activities do not crowd out the supervision provided by counterparties, creditors and investors.” [62] Financial regulation should be “based on a presumption of permission rather than a presumption of prohibition.” [63]

A section of one of Summers’ speeches [64] as Treasury Secretary is titled: “Providing a Strong Legal and Regulatory Framework for the Financial Markets.” However, the examples Summers gives of the public sector’s contribution to this “strong regulatory framework” are in fact the deregulatory acts he championed: the 1999 Financial Services Modernization Act which repealed the Glass-Steagall Act and the 2000 Commodity Futures Modernization Act. Summers appeared to view deregulation as the primary contribution the public sector could make to strengthen financial markets.

According to Summers, the goal of government policies should be to help financial corporations expand, and that was why deregulation was needed. He claimed that governments should implement “policies that help to expand the size of markets…That means that deregulation becomes that much more important, to ensure that government is not preventing or distorting the development of fast-growing markets. That is we worked so hard to pass the right kind of Financial Modernization legislation last year…”[65]

Robert Rubin, Summers’ mentor and predecessor as Treasury Secretary, relates in his memoir that “Larry thought I was overly concerned with the risks of derivatives.” Summers has recently explained his own lack of concern by saying “If we had known that derivatives markets would mushroom the way they did and that regulators would remain spectators, we would have acted.” [66] However, Summers’ rationale for deregulating the derivatives market was precisely so that it could expand and he took a lead role in sidelining regulators like Brooksley Born who wanted to act.

Summers’ opinion while at the Treasury Department was that public servants should work co-operatively with the financial institutions they are responsible for regulating: “By drawing on a spirit of cooperation between the private sector and the public sector, over the past 8 years this Administration has worked to provide the right framework for our financial industry to thrive.” [67]

During George Bush’s presidency, Summers was critical of the government’s lack of oversight of critical areas of the economy. Asked to explain his apparent change of attitude towards regulation, Summers said the following: “And so when things were pretty screwed up, and the dominant thrust of the policy had been of doing nothing, the inclination was much more on the activist side. But I don’t think it’s because I changed, I think it’s because the world changed.”[68]

Views on the Role of the Finance Industry in the US Economy

Summers promotes the concept of “a post-industrial age” where manufacturing is not key to prosperity. He has said that the strength of the US economy largely relies on the strength of its financial system. An expression he was fond of repeating as Treasury Secretary was: “Financial markets do not just oil the wheels of economic growth. They are the wheels.” [69][70]

For Summers, “modern competitive finance” is an area where the US excels: “No other financial market is so open to foreign competition or so quick to innovate, whether it be in the area of securitization, financial derivatives, high-yield debt, or equity finance”. He has particular praise for the US derivatives market, which he sees as “a powerful symbol of the kind of innovation and technology that has made the American financial system as strong as it is today.” In contrast, Warren Buffet likens derivatives to “time bombs, both for the parties that deal in them and the economic system. [71]

Summers identifies the well-being of US financial institutions with that of the overall economy: “In a very real sense, the financial system is the central nervous system of our economy. And just as the past dynamism of our financial sector has been central to America's current prosperity, so the future success of that sector will be very important to the well-being of the economy as a whole.” [72]

Recently, Summers has commented on the ways to address high unemployment job rate and the lack of economic growth. "This is a profoundly important problem for our society, but it's the task of economists to analyze it in a more bloodless way." [73] "Asked when that high unemployment would abate, he explained that it would depend upon "the pace of the economic recovery in terms of GDP" [Gross Domestic Product] and whether the formula that economists have historically used to predict job growth based on GDP would continue to be skewed by unusually high productivity. "Make your judgment about the GDP forecast over the next several years. Take your guess about whether the formula is going to snap back, or continue to be off, and you can form a view about the unemployment rate." Maybe things will restore to normal," he said -- in which case job growth would actually outpace GDP. "That would be my guess, though not one I would hold confidently." [74] "But asked if the country needs another stimulus, he replied: "I don't think framing the question in terms of a 'stimulus' is very helpful." He said he favored continuing unemployment insurance, new funding for local governments and investments in energy efficiency -- three major progressive goals. But beyond that, he said: "Is this the moment for some major new experiment in Keynesian pump-priming? Absolutely no." [75]

With respect to the growth of large American Banks, Summers opposes breaking huge banks into smaller institutions. "But that's not the important issue," Summers said during the interview, adding to his answer as to why the U.S. shouldn't break up megabanks. "[Observers] believe that it would actually make us less stable, because the individual banks would be less diversified and, therefore, at greater risk of failing, because they would haven't profits in one area to turn to when a different area got in trouble. And most observers believe that dealing with the simultaneous failure of many -- many small institutions would actually generate more need for bailouts and reliance on taxpayers than the current economic environment," he added. [76]

Views on Trade

Summers had worked as a consultant for the Coalition of Services Industries - a lobby group founded by American Express, Citibank and AIG - before he joined the Treasury Department. The Coalition was founded in the 1980’s to get an international agreement on trade in financial services. According to Harry Freeman, the American Express vice-president assigned to head this lobby group, the decision by Amex to spend unlimited funds on the lobbying campaign and hire Larry Summers and others “paid off.” [77]

As Treasury Secretary when he was speaking to a luncheon sponsored by the Coalition of Service Industries, Summers thanked participants on behalf of the Treasury Department for their “terrific co-operation” in advancing trade priorities that “the U.S. government and that U.S. industry share.” [78]

Summers has said that the most important issue that will affect the lives of Americans for the next fifty years is the country’s support for global integration and open markets. In advance of the World Trade Organization 1999 Ministerial in Seattle, Summers argued that while there is a strong political, economic, and national security case for trade, the benefits are undervalued. He gave as an example that Americans do not notice they are able to buy twice as many Christmas toys “because of our increased trade links with very poor countries who can make these things more cheaply.” [79]

In a 1999 speech to the insurance industry, [80], Summers boasted about the Clinton administrations’ negotiations of 240 new trade agreements, including NAFTA, and highlighted the World Trade Organization agreement on financial services in particular. This agreement committed countries to trade in the full range of financial products, including derivatives.

Views on Social Programs

Summers believes social assistance, unemployment insurance, and unions cause unemployment. Government assistance to the unemployed, in Summers’ view, provides both an incentive and the means for them not to work. He moderates these assertions by also saying that “It is, however, a great mistake (made by some conservative economists) to attribute most unemployment to government interventions in the economy or to any lack of desire to work on the part of the unemployed.” [81]

Role in the Enron Crisis

When he was about to take office as Treasury Secretary, Summers received a congratulatory letter from Ken Lay, the President of Enron Corporation. The letter was addressed “Dear Larry”. In his response addressed to “Ken”, Summers promised: “I’ll keep my eye on power deregulation and energy-market infrastructure issues.” [82]

During California’s energy crisis in 2000, Summers rejected the idea that energy companies like Enron were manipulating the market and gouging consumers. He opposed Governor Gray Davis’ plan for governments to intervene with price controls, claiming “This is classic supply and demand. The only way to fix this is ultimately by allowing retail prices to go wherever they have to go.” Summers also encouraged energy executives to compromise for the sake of preserving the potential for energy deregulation in other states. [83]

Summers has been criticized for allowing the “Enron Loophole” to be included in the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, a loophole that ensured the Commodity Futures Trading Commission could not regulate energy trading. In its review of original correspondence between Enron and Summers, Public Citizen has concluded Summers responses “marked a departure from previous Working Group consensus and indicated a sea change in the Clinton administration’s policy, suggesting the administration would not oppose Enron in its pursuit of legislation to further deregulate the energy trading business.” Public Citizen connected the Enron Loophole with the crisis California subsequently suffered: “Following passage of the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000, sponsored by Gramm and not opposed by the Clinton administration, Enron and other energy traders were allowed to operate unregulated power auctions that greatly enhanced their ability to manipulate deregulated electricity and natural gas markets.” [84]

Role in International Crises

As Undersecretary in the Treasury Department in the early 1990’s, Summers pressured Russia to institute rapid privatization and liberalization. He suggested that multilateral support, which would include IMF funds, would be withdrawn if these changes were not made fast enough. Reviewing the impacts of these prescriptions, Naomi Klein has written in The Shock Doctrine about the corrupt enrichment of oligarchs and the impoverishment of the general populace. Sharp rises in alcoholism, suicides, homicides, and homelessness resulted from what Klein describes as the “planned misery” Summers and others forced on Russia. [85]

Summers worked to strengthen the ability of the IMF to enforce neo-liberal policies on foreign countries. In his analysis of US influence on foreign countries’ economic policies, Edward Luce has written: “Led by Robert Rubin and Lawrence Summers, Mr Clinton’s economic team spent the decade adding heft to the International Monetary Fund’s often intrusive attempts to restructure exposed economies - from Mexico in 1994 to the victims of the Asian flu crisis in 1997. These countries had strayed from the orthodoxies of the Washington consensus and were required to don the hairshirt in recompense.” [86] In the South Asian financial crisis of the late 1990’s, Summers was the Treasury official sent to block efforts by Japan and other Asian countries to create a fund for a bailout. Korea, Indonesia, and Thailand were forced to deal with the IMF and conform with its policy directives to cut public spending, privatize, and open their economies to foreign companies. According to Mark Weisbrot, “The orders from Washington were clear: any bailout would have to go through the IMF, with results that turned out to be an economic and human disaster. [87] Former IMF economist Simon Johnson remembers having “the IMF in one room and the South Koreans in another, but Larry Summers was the guy dictating the conditions from a third.” [88]

Harvard

Summers became President of Harvard University in 2001 and resigned under pressure in 2006. While the Weekly Standard named Summers its "favorite university president"[89] his term as president was associated with a number of controversies, including:

- Derivative losses. Summers departed the Treasury in 2001 and went off to be the President of Harvard, where he ignored repeated warnings by expert staff and lost Harvard some $2 billion of its endowment funds, including $1 billion on toxic interest rate swaps. Read about it in the Boston Globe[90] and Bloomberg.[91]

In November 2013, Bloomberg Businessweek reports that the derivatives losses continue to mount:

The Larry Summers administration is still costing Harvard University. The school lost $345 million this fiscal year getting out of interest rate swaps it agreed to before the financial crisis, when Summers, then the university president, made bets on exotic debt derivatives.

The swaps losses were an increase from $134.6 million in 2012, and now add up to more than $1.25 billion since 2008, Bloomberg News reported. Harvard detailed the figures in its annual financial report (PDF), which showed its endowment, the nation’s largest, returning 11.3 percent to reach $32.7 billion. That’s a big improvement from 2012, when Harvard posted the financial performance in the Ivy League, losing 0.5 percent.

- Views on women. In 2005, Summers gave a speech speculating that the reason why women were underrepresented as tenured engineering and science professors was due to their unwillingness to work the long hours required, and “issues of intrinsic aptitude, and particularly of the variability of aptitude”. He argued that “socialization and continuing discrimination” were “lesser factors.” [93]

- Support for Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) at Harvard. Summers made a special effort to encourage the ROTC presence at Harvard. According to the campus newspaper, Summers “broke with precedent and spoke at the annual ROTC ceremony every year during his presidency in an effort to show support for students in the program and for expanded military access to the campus. [94]

- Harvard payment to settle case of Summers’ close friend, Professor Andrei Shleifer. Harvard paid $26.5 million to settle a suit after “a U.S. district court found Shleifer liable for conspiracy to defraud the U.S. government, and concluded that Harvard had breached its contract with the government.” Shleifer and his wife had invested in Russia at the same time that they were on contract with the government’s Agency for International Development, resulting in a conflict of interest. Faculty members were critical of the payment Harvard made to settle the case and the lack of disciplinary action taken against Shleifer. One professor said at a meeting with Summers “The outcome of the tawdry Shleifer affair...would have been unthinkable—unthinkable—during the last two presidencies, but is all too characteristic of the present malaise.” [95]

Tobacco

Larry Summers is mentioned in the tobacco-related research library.<tdo>resource_id=39135 resource_code=summers_lawrence search_term="Lawrence Summers"</tdo>

Background info

Summers was born November 30, 1954 in New Haven, Connecticut, and grew up in suburbs of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

He received a Bachelor of Science degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a PHD from Harvard. He worked in 1982 as part of President Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisers, and then returned to Harvard to teach.

In 1991, he took the position of vice president of development economics and chief economist of the World Bank.

From 1993 to 2001 he worked at the Treasury Department. In 1993, he was named as undersecretary of the treasury for international affairs. In 1995 he was promoted to deputy secretary of the treasury.

July 1999 - Confirmed as Secretary of the Treasury. (His signature appeared on U.S. paper currency as a result of holding this job.)

July, 2001 - Became president of Harvard University. He resigned in 2006 following a no-confidence vote by Harvard faculty.

Before he became Director of the National Economic Council in 2008, he taught at Harvard and worked as a part-time managing director at the hedge fund, D.E. Shaw. [96]

Previous Affiliations

- Member, Group of Thirty [97]

- Director, Teach for America

- Member, Global Development Program Advisory Panel, Gates Foundation [98]

- Policy Board (Chair), Harvard AIDS Institute [99]

- Board of the Brookings Institution

- Board of the Center on Global Development

- Board of the Institute for International Economics,

- Board of the Global Fund for Children’s Vaccines

- Board of the Partnership for Public Service.

- Member of the Council on Foreign Relations,

- Member of the Trilateral Commission

- Member of the Bretton Woods Committee

- Member of the Council on Competitiveness

- Member of the UNCTAD Panel of Eminent Persons. [100]

- Board of Governors, Eli and Edythe L. Broad Foundation [101]

Contact details

Articles & resources

Related Sourcewatch articles

References

- ↑ Felix Salmon, “Annals of rank hubris, Larry Summers edition, [1] Reuters, July 22, 2009.

- ↑ News release, President –Elect Barack Obama[2], November 24, 2008.

- ↑ Square Board, accessed April 30, 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 The National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in the United State, The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report, government report, January 2011.

- ↑ PBS' Frontline, The Warning, television report, October 20, 2009.

- ↑ U.S. Department of the Treasury, TREASURY DEPUTY SECRETARY LAWRENCE H. SUMMERS TESTIMONY BEFORE THE SENATE COMMITTEE ON AGRICULTURE, NUTRITION, AND FORESTRY ON THE CFTC CONCEPT RELEASE, testimony, July, 30, 1998.

- ↑ Commodity Futures Trading Commission, CFTC ISSUES CONCEPT RELEASE CONCERNING OVER-THE-COUNTER DERIVATIVES MARKET, press release, May 7, 1998.

- ↑ Commodity Futures Trading Commission, THE LESSONS OF LONG-TERM CAPITAL MANAGEMENT L.P., REMARKS OF BROOKSLEY BORN, CHAIRPERSON COMMODITY FUTURES TRADING COMMISSION CHICAGO KENT-IIT COMMODITIES LAW INSTITUTE, October 15, 1998.

- ↑ Public Citizen, Enron CEO Ken Lay's Correspondence with Treasury Secretaries, collection of correspondence, accessed September 10, 2013.

- ↑ Public Citizen, Trade Agreements Cannot be Allowed to Undermine Financial Regulation, organizational fact sheet, accessed September 10, 2013.

- ↑ PRWatch, Memorandum for Deputy Secretary Summers, U.S. Department of Treasury Correspondence, November 24, 1997.

- ↑ Stephen Labaton, CONGRESS PASSES WIDE-RANGING BILL EASING BANK LAWS, The New York Times, November 5, 1999.

- ↑ The President's Working Group on Financial Markets, Over-the-Counter Derivatives Markets and the Commodity Exchange Act, government report, November, 1999.

- ↑ Public Citizen, letter from Larry Summers to Ken Lay, letter correspondence, November 22, 1999.

- ↑ U.S. Senate, THE COMMODITY FUTURES MODERNIZATION ACT OF 2000, congressional record, January 2, 2001.

- ↑ Mark Gongloff, Larry Summers' Enron Connection Is Yet Another Reason Not To Make Him Fed Chairman, Huffington Post, August 5, 2013.

- ↑ Beth Healy, Harvard ignored warnings about investments, Boston Globe, November 29, 2009.

- ↑ Michael McDonald, John Lauerman and Gillian Wee, Harvard Swaps Are So Toxic Even Summers Won’t Explain (Update3), Bloomberg, December 18, 2009.

- ↑ Sam Stein, Larry Summers Cast As Dysfunctional Force In 'Revival,' Obama Insider Book, Huffington Post, November 15, 2010.

- ↑ Michael Hirsh, Does Larry Summers Have Integrity?, National Journal, August 5, 2013.

- ↑ Frontline, Interview: Joseph Stiglitz, PBS, October, 2009.

- ↑ Felix Salmon, Summers: “Inside Job had essentially all its facts wrong”, Reuters, January 27, 2012.

- ↑ Department of the Treasury – History

- ↑ Remarks by Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers to the Securities Industry Association, November 9, 2000.

- ↑ Remarks by Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers to the Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley, December 6, 2000.

- ↑ Dean Baker, “Summers at Treasury: What Would We Tell the Children?”, “The Huffington Post”, November 7, 2008.

- ↑ Statement by Treasury Secretary Lawrence H. Summers, Office of Public Affairs, Treasury Department, October 22, 1999.

- ↑ Robert Weissman and Harry Rosenfeld, “Sold Out: How Wall Street and Washington Betrayed America,” Wall Street Watch, March 2009, p. 17.

- ↑ Arianna Huffington, “Larry Summers: Brilliant Mind, Toxic Ideas”, Huffington Post, March 25, 2009.]

- ↑ Statement by Treasury Secretary Lawrency H. Summers Office of Public Affairs, Treasury Department, November 4, 1999.

- ↑ ”10 Years Later, Looking at Repeal of Glass-Steagall”, New York Times, November 12, 2009.

- ↑ Statement by Treasury Secretary Lawrence H. Summers,[3] Office of Public Affairs, Treasury Department, October 22, 1999.

- ↑ Lawrence H. Summers, "Toward a 21st Century Financial Regulatory System”, Office of Public Affairs, Treasury Department, October 5, 1999.

- ↑ Lawrence H. Summers, "Toward a 21st Century Financial Regulatory System”, Office of Public Affairs, Treasury Department, October 5, 1999.

- ↑ Congressional Oversight Panel, “Special Report on Regulatory Reform”, January 2009, p.20.

- ↑ [[4]]

- ↑ Lawrence Summers, Testimony before the Joint Senate Committees on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry and Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, June 21, 2000.

- ↑ [5]

- ↑ Frank Partnoy, F.I.A.S.C.O – Blood in the Water on Wall Street, 2009, pps. 267-268.

- ↑ PBS Transcript,“The Warning”, October 20, 2009.

- ↑ [6]

- ↑ PBS, Transcript of [ http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/warning/etc/script.html “The Warning”], October 20, 2009.

- ↑ Lawrence Summers, Treasury Deputy Secretary, “Testimony before the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry on the CFTC Concept Release”, Treasury Department, July 30, 1998.

- ↑ Lawrence Summers, Treasury Deputy Secretary, “Testimony before the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry on the CFTC Concept Release”, Treasury Department, July 30, 1998.

- ↑ Steve Korris, ”Official Tried in Vain to Avert Wall Street Catastrophe.”, The Madison-St. Clair Record, March 27, 2009

- ↑ Frank Partnoy, F.I.A.S.C.O – Blood in the Water on Wall Street, 2009, p. 164.

- ↑ PBS, Transcript of [ http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/warning/etc/script.html “The Warning”], October 20, 2009.

- ↑ Interview with Brooksley Born, Transcript, PBS, October 20, 2009.

- ↑ US Treasury Department, “Statement by Treasury Secretary Lawrence H. Summers”, December 14, 2000.

- ↑ President’s Working Group on Financial Markets,” Over-the-Counter Derivatives Markets and the Commodity Exchange Act”, November 1999.

- ↑ Bloomberg News, “Harvard Losing AAA Benefit in Market Shows Swap Risk”, March 3, 2009.

- ↑ President’s Working Group on Financial Markets, ”Over-the-Counter Derivatives Markets and the Commodity Exchange Act” November 1999.

- ↑ Lawrence Summers, Remarks to the Coalition of Service Industries and Congressional Economic Leadership Institute, Washington, DC., August 12, 1997.

- ↑ [“Times Topics - People - Summers, Lawrence H.”, New York Times. Accessed March 20, 2010.

- ↑ Lawrence Summers, “Rescuing and Rebuilding the US Economy: A Progress Report”, Speech to the Peterson Institute for International Economics, July 17, 2009.

- ↑ Paul Krugman, “Stimulus arithmetic (wonkish but important)”, New York Times, January 6, 2009.

- ↑ Louise Story, “A Rich Education for Summers (After Harvard)”, New York Times, April 5, 2009.

- ↑ Philip Rucker and Joe Stephens, “Top Economics Aide Discloses Income”, The Washington Post, April 4, 2009.

- ↑ Louise Story, “A Rich Education for Summers (After Harvard)”, New York Times, April 5, 2009.

- ↑ Louise Story, “A Rich Education for Summers (After Harvard)”, New York Times, April 5, 2009.

- ↑ Philip Rucker and Joe Stephens, “Top Economics Aide Discloses Income”, Washington Post, April 4, 2009.

- ↑ Remarks by Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers to the Securities Industry Association, November 9, 2000.

- ↑ Lawrence Summers, Remarks to the Coalition of Service Industries and Congressional Economic Leadership Institute, Washington, DC., August 12, 1997.

- ↑ Remarks by Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers to the Securities Industry Association, November 9, 2000.

- ↑ [ http://www.treas.gov/press/releases/ls922.htm Remarks by Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers to the Kennedy School of Government], September 27, 2000.

- ↑ Ryan Lizza, [ http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2009/10/12/091012fa_fact_lizza?currentPage=all “Inside the Crisis: Larry Summers and the White House Economic Team”], The New Yorker, October 12, 2009.

- ↑ [ http://www.ustreas.gov/press/releases/ls1005.htm Remarks by Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers to the Securities Industry Association], November 9, 2000.

- ↑ Ryan Lizza,“Inside the Crisis Larry Summers and the White House Economic Team”

- ↑ Lawrence Summers, “The United States and China at the Dawn of a New Century”, Remarks to the Asia Society Annual Dinner, October 12, 1999.

- ↑ Lawrence Summers, Remarks to the Coalition of Service Industries and Congressional Economic Leadership Institute, Washington, DC., August 12, 1997.

- ↑ Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway Annual Report for 2002

- ↑ Remarks by Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers to the Securities Industry Association, November 9, 2000.

- ↑ Dan Fromkin,"Stop Robert Rubin Before He Kills Again,", "Huffington Post," April 30, 2010.

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ Shahien Nasiripour, "Larry Summers Defends Megabanks, Says Too Many Small Banks Make U.S. Less Stable,", "Huffington Post," April 23, 2010.

- ↑ Harry L. Freeman, “The Role of Constituents in U.S. Policy Development Toward Trade in Financial Services”, Chapter 10, in Constituent Interests and U.S. Trade Policies by Alan V. Deardorff, Robert Mitchell Stern, 1998, p. 184.

- ↑ Lawrence Summers, Remarks to the Coalition of Service Industries and Congressional Economic Leadership Institute, Washington, DC., August 12, 1997.

- ↑ Lawrence Summers, “The Case for American Support for Open Markets”, Remarks to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Washington, DC, November 10, 1999.

- ↑ Lawrence Summers, “Issues for the Financial Services Industry in 1999”, Remarks to Property-Casualty Insurers Industry Forum New York, NY, January 13, 1999.

- ↑ Lawrence Summers, “Unemployment”, The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, accessed March 15, 2010.

- ↑ Associated Press, “Ex-Treasury Chief Told Lay He’d Watch Key Issues”, March 8, 2002

- ↑ Kurt Eichenwald, Conspiracy of Fools: A True Story, December 2005, pps. 403 and 411.

- ↑ Public Citizen News Release, “Recently Released Treasury Documents Chronicle Enron’s Influence in Washington”, April 28, 2003.

- ↑ Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine- the Rise of Disaster Capitalism, pps. 262-294.

- ↑ Edward Luce, “Self-doubt tarnishes Brand America,” Financial Times, December 29, 2009.

- ↑ Mark Weisbrot, “Globalization on the Ropes”, Harper's Magazine, May 2000.

- ↑ Edward Luce, “Self-doubt tarnishes Brand America,” Financial Times, December 29, 2009.

- ↑ James Traub, “Harvard Radical”, The New York Times, August 24, 2003.

- ↑ Beth Healy, Harvard ignored warnings about investments, Boston Globe, November 29, 2009.

- ↑ Michael McDonald, John Lauerman and Gillian Wee, Harvard Swaps Are So Toxic Even Summers Won’t Explain (Update3), Bloomberg, December 18, 2009.

- ↑ Nick Summers, Dog Days of Summers Cost Harvard $345 Million, Bloomberg Businessweek, November 11, 2013.

- ↑ Lawrence Summers, “Remarks at NBER Conference on Diversifying the Science & Engineering Workforce,” January 14, 2005.

- ↑ “After Harvard Leaders' Absence, ROTC Supporters Fear Return to Icy Relations,” [7] June 22, 2007.

- ↑ “’Tawdry Shleifer Affair’ Stokes Faculty Anger Toward Summers,” [8], The Crimson, February 10, 2006.

- ↑ Lawrence H. Summers, “Biography,” [9] accessed March 26, 2010.

- ↑ Group of Thirty Members, organizational web page, accessed December 5, 2013.

- ↑ Program Advisory Panels Announced by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, accessed December 9, 2007.

- ↑ Policy Board, Harvard Aids Institute, accessed October 13, 2008.

- ↑ Lawrence H. Summers, “Biography”, Harvard, accessed March 26, 2010.

- ↑ 2009/10 Annual Report, Eli and Edythe L. Broad Foundation, accessed 4 February 2011.

External resources

- "Biography: Lawrence H. Summers", undated, accessed September 2004.

- Ryan Lizza, “Inside the Crisis Larry Summers and the White House Economic Team”, The New Yorker, October 12, 2009.

- Arianna Huffington, “Larry Summers: Brilliant Mind, Toxic Ideas”, Huffington Post, March 25, 2009.