Waste Management

|

Find the privatizers and profiteers at OutsourcingAmericaExposed.org. |

|

Learn more about corporations VOTING to rewrite our laws. |

Waste Management, Inc. (known as Waste Management or WM) is a publicly-traded (NYSE:WM) for-profit waste management company headquartered in Houston, Texas and is the largest waste collection corporation in North America. It is in the business of waste collection and transfer, recycling and resource recovery, and waste disposal for residential, commercial, industrial and municipal customers in North America.[1]

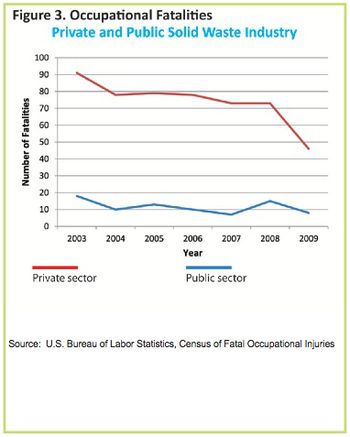

In the United States, waste management services have traditionally been provided by municipalities and public employees, but the privatization of this sector has accelerated.[2] According to a 2007 survey of local governments, some 50 percent of solid waste management is now provided by major for-profit firms like Waste Management.[3] WM has been a driving force in the privatization of these services. WM workers are paid significantly less than their public sector counterparts.[4] The number of deaths in this dangerous industry was higher among workers at for-profit companies than among public sector workers from 2003 to 2009.[5]

In 2005, WM paid $30.8 million to the Securities and Exchange Commission to settle allegations of "egregious" and sustained accounting fraud. (See below).[6]

WM owns and/or operates 252 landfill sites (as of its 2014 annual report), which the company says is the largest network of landfills in its industry, and 298 transfer stations, and employs approximately 39,800 people.[7] In general, landfills and incinerators are major producers of greenhouse gases and toxic chemicals that pollute the air and groundwater. Landfills produced 17.5 percent of total anthropogenic methane emissions in the United States in 2011, the third largest contribution in the country, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA),[8] although they were the largest contributor, producing 34 percent of total methane emissions, from 1990 to 2003.[9][10] According to the EPA, "Pound for pound, the comparative impact of CH4 [methane] on climate change is over 20 times greater than CO2 [carbon dioxide] over a 100-year period."[11]

Although WM has touted "green" campaigns in its PR (in addition to its green and yellow logo), the company lists climate change legislation as a potential threat to its operations and cash flow in its annual report,[1] and it has lobbyists working on these issues at the federal level (see below for more).[12] Some WM operated or owned landfills have been designated Superfund sites for hazardous waste that needs to be mitigated, and WM has participated in various efforts to alter or cap landfills.[13]

According to its 2014 annual report, WM employed approximately 39,800 people (8,500 of whom work under collective bargaining agreements), down from 42,700 in 2013.[14][15][1]

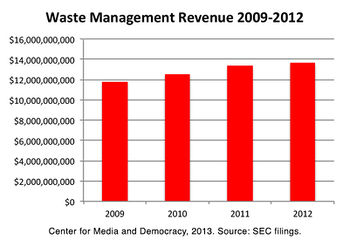

PROFITS : In its 2014 fiscal year, WM took in just under $14 billion in total revenues, with net profits of $1.3 million.[14][7]

Contents

- 1 Business Model and History

- 2 Controversies

- 2.1 Waste Management Sued by SEC, Which Alleged "One of the Most Egregious Accounting Frauds We Have Seen"

- 2.2 Accounting Scandal and Failed Merger Leads to Class Action Suit

- 2.3 Contract Failures

- 2.4 Other Health and Safety Issues

- 2.5 Dirty Industry Contributes to Climate Change; WM Views Limits on Greenhouse Gases as a Threat

- 3 Ties to the American Legislative Exchange Council

- 4 Political Activity

- 5 Corporate Subsidies

- 6 Fine Print Follies

- 7 Personnel

- 8 Contact Information

- 9 Resources and Articles

Business Model and History

BUSINESS MODEL: WM is a holding company, and all of its operations are conducted through subsidiaries. The company owns and/or operates 267 landfill sites, as of its 2013 annual report, which the company says is the largest network of landfills in its industry.[15] It manages 300 transfer stations that consolidate, compact, and transport waste to the landfills. Through its former subsidiary, Wheelabrator Technologies, Inc. (sold in 2014 for $1.95 billion), WM operated 17 waste combustion plants that recover gas from decomposing waste in landfills and use it in generators to make electricity.[15][7] WM also operates 126 recycling facilities, according to the company's 2014 annual report, and acquired the recycling facilities company Greenstar, LLC in January 2013.[7]

WM is involved in fracking services and other energy industries through its Energy Services segment, which "provides specialized environmental management and disposal services for oil and gas exploration and production operations."[7] WM division FlyAshDirect contracts with coal electricity providers such as American Electric Power to market and dispose of fly ash, a coal combustion waste product.[16]

FOUNDING: WM was founded in Chicago in 1968 and went public in 1971.[17] In 1998, it was acquired by USA Waste Services, Inc., which then changed its name to Waste Management, Inc. USA Waste Services "was incorporated in Oklahoma in 1987 under the name 'USA Waste Services, Inc.' and was reincorporated as a Delaware company in 1995,” according to WM’s 2012 annual report.[1] However, when it was purchased by USA Waste Services in 1998, WM already had a reputation as “the least law abiding waste hauler in America” (according to a study of the waste hauling industry in 1986 by the Council on Economic Priorities) and a “record of environmental violations unparalleled among waste haulers” (according to Rachel's Hazardous Waste News in 1989).[18] Greenpeace launched a campaign against the company in 1991 for what the Los Angeles Times summarized as alleged “price fixing, antitrust violations, intimidation, violation of federal and state pollution laws resulting in millions of dollars in fines, and the deliberate siting of landfills and incinerators in poor communities without the wherewithal to fight back.”[19]

In 2010, Waste Management, Inc. purchased a controlling share in Garick LLC, a company that produces, packages, and transports compost, soils, and mulches, and provides consulting on the composting industry.[20]

Controversies

Waste Management Sued by SEC, Which Alleged "One of the Most Egregious Accounting Frauds We Have Seen"

In 2002, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) brought a lawsuit against the founder and five other former top officers of Waste Management Inc., charging them with "perpetrating a massive financial fraud lasting more than five years," according to an SEC press release regarding the litigation.[21]

The complaint charged that the defendants--Dean L. Buntrock, founder, chairman and former CEO; Phillip B. Rooney, president, director, COO and former CEO; James E. Koenig, executive vice president and CFO; Thomas C. Hau, corporate controller and chief accounting officer; Herbert Getz, general counsel and secretary; and Bruce D. Tobecksen, vice president of finance--allegedly "engaged in a systematic scheme to falsify and misrepresent Waste Management's financial results between 1992 and 1997." The SEC alleged in the complaint that defendants "fraudulently manipulated the company's financial results to meet predetermined earnings targets . . . in violation of anti-fraud, reporting, and record-keeping provisions of the federal securities laws." The defendants allegedly inflated profits by $1.7 billion, reaping nearly $29 million in "ill-gotten gains" from annual bonuses and insider trading, while "defrauded investors" lost more than $6 billion, according to the press release.[21]

Then-associate director of the SEC's Division of Enforcement, Thomas C. Newkirk, called it "one of the most egregious accounting frauds we have seen," stating, "For years, these defendants cooked the books, enriched themselves, preserved their jobs, and duped unsuspecting shareholders."[21]

The defendants were allegedly aided in their fraud by the company's long-time auditor, the accounting firm Arthur Andersen LLP, which repeatedly issued unqualified audit reports on the company's materially false and misleading annual financial statements, according to the SEC allegations.[21] In 2001, the SEC fined Arthur Andersen $7 million for its role in the audits, prior to the complaint against WM's top officials, according to the Wall Street Journal.[22]

In 2005, the U.S. District Court in Chicago entered final judgments in the case, permanently barring Buntrock, Rooney, Hau, and Getz from acting as an officer or director of a public company and requiring them to pay $30.8 million in "disgorgement, prejudgment interest, and civil penalties," according to a 2005 SEC press release.[23]

Accounting Scandal and Failed Merger Leads to Class Action Suit

Based in part on the accounting scandal described above as well as a failed merger, shareholders filed more than 30 lawsuits against WM that were consolidated into a class-action suit in July 1999. The lawsuits stemmed from accounting fraud perpetrated between 1992 and 1999. Around the same time, between 1996 and 1999, WM went through five CEOs, and its stock lost more than $25 billion in value. According to CNN Money, "The turmoil allowed a smaller company, USA Waste Services, to take over the crippled giant in a merger that later failed miserably and resulted in more than $1.2 billion in charges."[24]

In the end, Waste Management agreed to pay $457 million to settle the allegations that it had violated federal securities laws in connection with its 1998 merger with USA Waste Services and its statements about financial performance in the first three quarters of 1999. In the summer of 2000, the company and its auditing firm, Arthur Andersen, also "agreed to pay $229 million to settle another class-action suit about questionable accounting practices," according to CNN Money.[25]

Contract Failures

Mobile, AL Claims WM Underpaid Royalties to City (2013): In August 2013, the Solid Waste Authority of Mobile, Alabama claimed that WM was "in breach of contract" after it found "a discrepancy between the tons Waste Management reports to the Alabama Department of Environmental Management compared to what it reports to the city." The city found that WM had only reported about half of its total volume and had underpaid royalties, and declared that WM might be replaced within three months.[26] WM promptly sued the city authority for $75,000 in response, alleging that "the authority failed to negotiate changes in pricing due to a variety of factors including increased fuel costs, regulatory changes, and capital improvements," according to the Alabama Press-Register. Waste Management also claimed that the city underpaid it, instead of the other way around, despite the dramatic differences in reported garbage.[27]

WM Division Releases Ash into Brook and Wetlands in MA: In May 2011, Waste Management's Wheelabrator division agreed to pay $7.5 million, the "highest ever for a state case arising out of environmental violations," in a settlement with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for "a host of environmental violations," according to the Eagle-Tribune. The company admitted no wrongdoing in settling the case with the state. Included in the settlement was $2 million in civil penalties for multiple environmental violations. State investigators at the Department of Environmental Protection found that Wheelabrator committed multiple violations of the Hazardous Waste Management Act and the Clean Water Act at its trash incineration plants in North Andover, Saugus, and Millbury. The violation at Wheelabrator Millbury involved the release of 15,000 gallons of ash water and 450 cubic yards of ash into a brook and wetlands adjacent to a Shrewsbury landfill, as well as into the air (due to a hole in the roof and side wall of the plant's ash house).[28] Incinerator fly ash often contains high concentrations of heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, copper and zinc as well as small amounts of dioxins and furans.[29]

Waste Management Overcharges Florida City by $176,000 (2008-2009): In January 2010, city officials in Delray, Florida ordered an audit of the city's billing system and contract with Waste Management after Ken MacNamee, a Delray resident, found that Waste Management had "apparently underpaid the city by $52,989 in commercial franchise fees," according to the Sun Sentinel. He also found that there was a difference in the number of residential customers that Waste Management serviced and the number of residents the city was billing. As a result, MacNamee estimated that the city had overpaid Waste Management by at least $176,000 for the years from 2008 to 2009.[30]

Other Health and Safety Issues

Solid waste collection is by its nature a dirty, dangerous industry. A search of the United States Department of Labor Occupation Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) database shows more than 300 safety violations at Waste Management, Inc., and subsidiary locations. Dozens of the nearly two hundred inspections during a ten year period (from August 2003 to August 2013) stemmed from accidents and complaints.[31]

According to the National Institute for Occupations Safety and Health (NIOSH):

- "The private and public solid waste industry recorded 599 fatal traumatic occupational injuries between 2003 and 2009 -- an average of 85 fatalities each year . . . Over 85% of these fatalities were attributed to the private sector[,] which experienced a substantial drop in the number of fatalities in 2009. The number of fatalities in the public sector has remained relatively unchanged during this period.

- "Transportation incidents, such as collisions and rollovers[,] were the leading events for occupational fatalities in all 3 industry groups. Collection workers have been struck and killed by other motorists. Contact with objects and equipment was the second leading cause of fatalities in each of the industry groups. This category includes being struck by, struck against[,] or caught in objects and equipment."[5]

Dirty Industry Contributes to Climate Change; WM Views Limits on Greenhouse Gases as a Threat

The waste industry is destructive, exploitative, and expensive, according to a 2013 study that does not name or focus on WM but looks at the industry as a whole. For-profit companies invest in the most common methods of disposal -- landfills and incinerators -- which are profitable, but contribute heavily to pollution and climate change. Not only do landfills produce 34 percent of methane emissions in the U.S., by some reports, but they generate dioxins and other substances designated as "known human carcinogens."[32] WM owns and operates 269 landfills in the United States, out of approximately 1,900 municipal solid waste landfills in the country,[33] all of which contribute to global warming.

WM tells investors that its profits would be affected by any new regulations geared toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions at the state or federal level, as reflected in the company's 2012 SEC filings. WM calls "stringent government regulations" that "govern environmental protection, health, safety, land use, zoning, transportation and related matters" a threat to its bottom line, as well as any potential climate change legislation which might have a "material adverse effect on our results of operations and cash flow".[1] It lobbies on these issues at the federal level, as shown by lobbying reports filed with the U.S. Congress.[34]

Ties to the American Legislative Exchange Council

Waste Management has been a corporate funder of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), and has held a leadership role as ALEC State Chair of Alabama.[35][36]

WM was a "private sector" leader of ALEC in the mid-1990s as ALEC was peddling "Enabling Legislation for Public-Private Infrastructure Partnerships," which specifically promoted outsourcing the management of solid waste facilities and related infrastructure to for-profit firms, according to ALEC’s 1996 Sourcebook of American State Legislation.[37] See ALEC Corporations for more.

| About ALEC |

|---|

ALEC is a corporate bill mill. It is not just a lobby or a front group; it is much more powerful than that. Through ALEC, corporations hand state legislators their wishlists to benefit their bottom line. Corporations fund almost all of ALEC's operations. They pay for a seat on ALEC task forces where corporate lobbyists and special interest reps vote with elected officials to approve “model” bills. Learn more at the Center for Media and Democracy's ALECexposed.org, and check out breaking news on our ExposedbyCMD.org site.

|

Political Activity

WM has spent more than $12.5 million on lobbying at the federal level since 1998 ($650,000 in 2014, $1,240,000 in 2013, $1,060,000 in 2012, $780,000 in 2011, $880,000 in 2010, $980,000 in 2009, and $840,000 in 2008), according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Among the lobbying firms hired by WM is New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s former firm, Bracewell & Giuliani LLP.[38] The company has lobbied on issues pertaining to hazardous and solid waste, taxes, environment and Superfund toxic waste legislation, transportation, trucking and shipping, energy and nuclear power, and government issues (specifically, sustainability requirements in federal contracts).[39]

WM also lobbied the U.S. House of Representatives, the U.S. Senate, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency about "climate change for landfills and WTE" (waste to energy) in 2013, according to a lobbying report filed with the U.S. Congress.[40][41]

WM reported $290,300 in contributions for the 2014 election cycle, with the majority going to republican candidates and groups, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.[42]

WM spent $536,543 in the 2012 election cycle, with 59 percent of contributions going toward Republican candidates and 41 percent to Democrats.[43]

At the state level, WM and its employees spent a total of over $5.8 million from 2003 to 2012 in contributions toward candidates, party committees, and ballot measures, according to the National Institute on Money in State Politics.[44] It has hired 267 lobbyists in 34 states from 2003 to 2012, according to the same source.[45]

Corporate Subsidies

According to Subsidy Tracker, a project of Good Jobs First, WM and some of its state-based subsidiaries received more than $32.6 million in corporate subsidies in Arizona, California, Maine, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin from 1997 to 2014. (Availability of data varies from program to program, so the total subsidies received may be higher.) This includes grants, low-cost loans, tax credits and rebates, property tax abatement, and training reimbursement. WM has also received millions in "enterprise zone" tax breaks in Arizona, California, and Maryland.[46]

Fine Print Follies

"Risk Factors" in SEC Filings

In its SEC filings, Waste Management, Inc. cites government regulation and other aspects of the waste management sector as “risk factors” that may affect its business and future prospects. These risk factors often show the incentives the company has to influence public policy and the direction its advocacy could take, because congressional lobby disclosure rules do not require sufficient detail for the public to determine what particular issues within proposed legislation a company like WM is pushing for. Among other issues, Waste Management cites environmental regulation, changing preferences that affect its profitability (e.g. alternatives to landfill disposal), and labor unions as threats to its business.[1]

WM states that "stringent government regulations" that "govern environmental protection, health, safety, land use, zoning, transportation and related matters," as well as any potential adoption of climate change legislation, threaten its future performance. For example:[1]

- "Our operations are subject to environmental, health and safety laws and regulations . . . that may result in significant liabilities. There is risk of incurring significant environmental liabilities in the use, treatment, storage, transfer and disposal of waste materials. Under applicable environmental laws and regulations, we could be liable if our operations cause environmental damage to our properties or to the property of other landowners, particularly as a result of the contamination of air, drinking water or soil. . . . Additionally, we could be liable if we arrange for the transportation, disposal or treatment of hazardous substances that cause environmental contamination. . . ."

- "The adoption of climate change legislation or regulations restricting emissions of 'greenhouse gases' could increase our costs to operate. Our landfill operations emit methane, identified as GHG. Efforts to curtail the emission of GHGs to ameliorate the effect of climate change could advance on the federal, regional or state level, and should comprehensive climate change legislation be enacted, we expect it to impose costs on our operations."[1]

The company also mentions changing preferences and technology (i.e., a propensity to recycle more) as a hindrance to its business:[1]

- "Increasing customer preference for alternatives to landfill disposal and waste-to-energy facilities could reduce our ability to operate at full capacity and cause our revenues and operating results to decline."

- "Developments in technology could trigger a fundamental change in the waste management industry, as waste streams are increasingly viewed as a resource, which may adversely impact volumes at our landfills and waste-to-energy facilities and our profitability."[1]

WM highlights unions as a major threat:[1]

- "Our operating expenses could increase as a result of labor unions organizing or changes in regulations related to labor unions. Labor unions continually attempt to organize our employees, and these efforts will likely continue in the future. Certain groups of our employees are currently represented by unions, and we have negotiated collective bargaining agreements with these unions. Additional groups of employees may seek union representation in the future, and, if successful, the negotiation of collective bargaining agreements could divert management attention and result in increased operating expenses and lower net income. If we are unable to negotiate acceptable collective bargaining agreements, our operating expenses could increase significantly as a result of work stoppages, including strikes. Any of these matters could adversely affect our financial condition, results of operations and cash flows."[1]

WM's involvement in the oil and gas sector means its business may also be affected by changes in energy prices and regulations on fracking and other extraction industries:

- "Energy Services business demand may also be adversely affected if drilling activity slows due to industry conditions beyond our control, in addition to changes in oil and gas prices. Changes in laws or government regulations regarding GHG emissions from oil and gas operations and/or hydraulic fracturing could increase our customers’ costs of doing business and reduce oil and gas exploration and production by customers. Recently, there has been increased attention from the public, some states and the EPA to the alleged potential for hydraulic fracturing to impact drinking water supplies. There is also heightened regulatory focus on emissions of methane that occur during drilling and transportation of natural gas, as well as protective disposal of drilling residuals. Increased regulation of oil and gas exploration and production and new rules regarding the treatment and disposal of wastes associated with exploration and production operations could increase our costs to provide oilfield services and reduce our margins and revenue from such services."[7]

Personnel

CEO

David P. Steiner is president and CEO of Waste Management (WM). He became CEO and a director in March 2004, and president in June 2010.[47] Steiner succeeded A. Maurice Myers, who had taken over WM's leadership in November 1999 after it experienced one of the worst accounting scandals in U.S. corporate history, when four of its top executives, in the words of the American Institute of CPAs, "cooked the company's books to meet predetermined earnings targets."[48] With Steiner at the helm, Waste Management settled the case with the SEC for $26.8 million in 2005, and picked up "the bulk of the penalties against all four men," according to the Chicago Tribune.[49]

David Steiner has been with Waste Management since November 2000, when he was hired as vice president and deputy general counsel. According to the Houston Business Journal, in 2000 Steiner "interviewed at multiple companies before finally narrowing his choice down to Waste Management Inc. and Enron Corp."[50] He was promoted to WM's senior vice president, general counsel, and corporate secretary in July 2001; and was elected chief financial officer in April 2003.[51]

Steiner led Waste Management's $6.7 billion hostile takeover bid for its rival, Republic Services, which was abandoned when the financial crisis hit in the fall of 2008. The attempt, which Bill Gates' investment arm called "ill timed and poorly conceived,"[52] led Forbes magazine to call Waste Management "the bully of garbage collection."[53]

Under Steiner's leadership, Waste Management's labor relations policies have taken a hard-line turn. Teamsters Local 70 secretary-treasurer Chuck Mack told The Seattle Times in 2007 that a formerly "pretty good relationship" with WM "changed in recent years when the company became more ideological on certain issues" such as health care and the right to strike. "They are large enough and wealthy enough to drive their agenda economically and spend what they need to spend to starve people out and bring in replacement workers. Whatever they need to do, they show a willingness to do it."[54]

In 2006, Waste Management workers in New York City went out on a nearly four month strike after months of heated negotiations over health and pension benefits and overtime.[55] WM, which had imposed a contract before the strike even though employees had rejected it, brought in temporary replacement workers. [56] The same week that New York City Waste Management employees struck, so did workers in Prince George's County (MD), the District of Columbia, California, Washington and Colorado.[57]

In 2007, under Steiner's leadership, Waste Management brought in permanent "replacement workers" during a strike in Los Angeles, replacing "in one week" some workers who, according to the union, had been with the company for 30 years.[58] In 2008, Milwaukee Teamsters charged Waste Management with threatening employees during a contract negotiation even though they had "always negotiated in good faith for more than 30 years."[59]

The company again brought in "replacement workers" during a bitter strike in Seattle in 2012.[60] During a union organizing campaign in San Diego in 2013, according to the Teamsters, Waste Management "brought in workers from other locations whose sole purpose was to try to bust the union drive, intimidate workers and give false information about organizing attempts at other facilities."[61] WM has also been accused of retaliating against low-paid immigrant union members in its East Bay recycling centers.[62]

Steiner has also led a determined public relations effort at Waste Management. Within a few years of his becoming CEO, the company was spending $25 million to $30 million a year on print and TV advertisements targeting "influencers," according to the New York Times. "We can't say our demographic is retired Americans, or 18-to-30 year old women, The Times quoted Steiner as saying, "we need the 48-year-old politician, and we need his 24-year-old constituent. And remember, those influencers may also have day jobs as purchasing agents."[63]

Despite driving a hard bargain over wages and benefits with Waste Management's employees, Steiner himself received approximately $67 million in compensation from WM from 2006-2014; between 2005 and 2014, Steiner's total compensation increased by 192 percent.[64][65] Steiner's total compensation for fiscal year 2014 was $10,770,856. This included a base salary of $1,186,785, $5,328,822 in stock awards, $1,233,147 in option awards, $2,626, $232,022,505 in incentive compensation, and $395,597 in other compensation, including $232,022 in personal use of company aircraft.[65]

Prior Years:

Steiner's base salary for the fiscal year 2013 was $1,149,616. He also received $5,692,630 in stock awards, $1,201,794 in option awards, $2,387,194 in incentive compensation, and $295,348 in other compensation, for a total compensation of $10,726,582.[15] In addition, Steiner received cash and equity awards of $247,874 for the fiscal year ended September 28, 2012 from TE Connectivity (formerly Tyco), on whose board he has been since June 2007;[66] and $236,165 in compensation for the year ended May 31, 2013 from FedEx Corporation, on whose board he has been since 2009.[67]

Leadership

WM's key executives received compensation worth $26,836,825 in 2014, up from $20,575,335 the previous year. Between 2008 and 2014, compensation of key executive totaled $117,716,184.[1][65]

As of July 2015:[68]

- David P. Steiner - President and Chief Executive Officer

- FY2014 Compensation: $10,770,856. This included $232,022 in personal use of company aircraft.[65]

- James E. Trevathan - Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer

- FY2014 Compensation: $3,175,877. This included $26,273 in personal use of company aircraft.[65]

- James C. Fish, Jr. - Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer

- FY2014 Compensation: $2,980,694. This included $4,033 in personal use of company aircraft.[65]

- Puneet Bhasin - Senior Vice President, Corporate Operations, President, WM Recycle America, L.L.C.

- Barry H. Caldwell - Senior Vice President Corporate Affairs and Chief Legal Officer

- Jeff M. Harris - Senior Vice President, Field Operations

- FY2014 Compensation: $2,546,245[65]

- John J. Morris, Jr. - Senior Vice President, Field Operations

- FY2014 Compensation: $2,444,759[65]

- Mark Schwartz - Senior Vice President, Human Resources

Board of Directors

As of July 2015:[69]

- W. Robert Reum, Non-Executive Chairman Waste Management; Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer, Amsted Industries Inc.

- David P. Steiner, President & CEO, Waste Management, Inc.

- Bradbury H. Anderson, Former Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, Best Buy Company, Inc.

- Frank M. Clark, Jr., Former Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, ComEd

- Andrés Gluski, President and Chief Executive Officer, The AES Corporation

- Patrick W. Gross, Chairman, The Lovell Group

- Victoria Holt, President and Chief Executive Officer of Proto Labs, Inc.

- John C. "Jack" Pope, Chairman, PFI Group

- Thomas H. Weidemeyer, Former Senior Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, United Parcel Service, Inc. and President of UPS Airlines

Contact Information

WM Headquarters

1001 Fannin, Suite 4000

Houston, Texas 77002

Phone: (713) 512-6200

Web: http://www.wm.com/index.jsp

Blog: http://thinkinggreen.wm.com

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/WasteManagement

Twitter: http://twitter.com/WasteManagement

Resources and Articles

Related SourceWatch Articles

Related PRWatch Articles

- Sara Jerving, New Toxic Sludge PR and Lobbying Effort Gets Underway, PRWatch, March 16, 2012.

- Sheldon Rampton, Green Garbage Trucks, PRWatch, February 14, 2008.

- Diane Farsetta, Greenwashing, or "Positioning Environmentalism", PRWatch, May 15, 2007.

External Articles

- Claudia H. Deutsch, A Garbage Hauler Tidies Up Its Image, New York Times, February 7, 2008.

- Environmental Research Foundation, Waste Management, Rachel's Hazardous Waste News, Issue #15, February 7, 1989. Calls Waste Management "the nation's largest polluter."

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 Waste Management, Annual Report/Form 10-K, SEC filing, February 14, 2013.

- ↑ Supreme Court Justice John Roberts, U.S. Supreme Court, Majority Opinion in re: UNITED HAULERS ASSOCIATION, INC., ET AL. v. ONEIDA-HERKIMER SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY ET AL., decision, April 30, 2007, p. 1.

- ↑ International City/County Management Association, Profile of Local Government Service Delivery Choices, survey, 2007.

- ↑ Kristen Mack, Emanuel's 'managed competition' push goes into full swing on recycling pickups, Chicago Tribune, September 30, 2011.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Solid Waste Industry, U.S. federal government agency fact sheet, March 2012. See also U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries: Fatal occupational injuries to private sector wage and salary workers, government workers, and self-employed workers by industry, All U.S., 2012 - table, federal government agency report table, August 22, 2013.

- ↑ U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Waste Management Founder and Three Other Former Top Officers Settle SEC Fraud Action for $30.8 Million, press release, March 26, 2002.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Waste Management, "2014 Annual Report, Form 10-K," SEC filing, March 26, 2015 (starting on pdf page 77).

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, INVENTORY OF U.S. GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS AND SINKS 1990-2011, Chapter 8: Waste, federal government agency report, April 12, 2013, p. 8-1.

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, INVENTORY OF U.S. GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS AND SINKS: 1990 – 2003, federal government agency report, April 15, 2005, p. 261.

- ↑ Veronica K. Figueroa, Kevin R. Mackie, Nick Guarriello, and C. David Cooper, [A Robust Method for Estimating Landfill Methane Emissions], Journal of Air & Waste Management Association, August 2009, Volume 59, pp. 925–935.

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Overview of Greenhouse Gases: Methane Emissions, federal government agency website, accessed October 2013.

- ↑ Bracewell & Giuliani, LLP, Lobbying Report for client Waste Management, federal lobbying report, January 1 - March 31, 2013.

- ↑ See, e.g., U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Superfund Site Progress Profile: RIVER ROAD LANDFILL (WASTE MANAGEMENT, INC.), federal government website, updated October 24, 2013.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Waste Management Inc., Bloomberg, company profile, accessed July 22, 2014.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Waste Management, Annual Report 2013, corporate report, accessed July 22, 2014.

- ↑ Waste Management, "Waste Management Wins Environmental Services Contract with American Electric Power," press release, November 13, 2013.

- ↑ Company Overview of Waste Management Inc., prior to acquisition by USA Waste Services Inc., Bloomberg BusinessWeek, October 28, 2013.

- ↑ Funding for Environmentalists, Rachel’s Hazardous Waste News #115, February 7, 1989.

- ↑ Bob Secter, Greenpeace Assails Record of Waste Management Inc., Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1991.

- ↑ John Funk, Waste Management Inc. buys majority interest in Garick LLC, maker of organic lawn and garden products, Cleveland.com, September 1, 2010, accessed April 30, 2011.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Waste Management Founder, Five Other Former Top Officers Sued for Massive Fraud, press release, March 26, 2002.

- ↑ SEC Fines Arthur Andersen $7 Million In Relation to Waste Management Audits (sub. req'd., text available here, Wall Street Journal, June 20, 2001.

- ↑ U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Waste Management Founder and Three Other Former Top Officers Settle SEC Fraud Action for $30.8 Million, press release, August 29, 2005.

- ↑ Julie Creswell, Scandal Hits -- Now What? Before Enron there was Waste Management. Here's how it came back from the brink, CNNMoney, July 7, 2003.

- ↑ Waste Management settles, CNNMoney, November 7, 2001.

- ↑ John Sharp, "City, Solid Waste Authority could cease landfill business with Waste Management," Alabama Press-Register, August 15, 2013. Accessed July 22, 2014.

- ↑ John Sharp, "Attorney: Waste Management engaging in 'bullying tactics' after filing lawsuit against Mobile Solid Waste Authority," Alabama Press-Register, August 27, 2013. Accessed July 22, 2014.

- ↑ Brian Messenger, Wheelabrator agrees to pay $7.5 million for violations, Eagle-Tribune, May 3, 2011.

- ↑ Chan, Chris Chi-Yet (1997). "Behaviour of metals in MSW fly ash during roasting with chlorinating agents" (PDF). Chemical Engineering Department, University of Toronto.

- ↑ Maria Herrera, Delray To Study Garbage Contract, Sun Sentinel, January 28, 2010.

- ↑ Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Waste Management, OSHA establishment data, accessed August 2013. (Note: Some of the results are public waste management authorities and are not counted in the total.)

- ↑ Partnership for Working Families, Transforming Trash in Urban America, organizational report, July 2013.

- ↑ National Solid Waste Management Association, Municipal Solid Waste Landfill Facts, trade association publication, October 2011.

- ↑ Bracewell & Giuliani, LLP, Lobbying Report for client Waste Management, federal lobbying report, January 1 - March 31, 2013.

- ↑ American Legislative Exchange Council, 1992 Annual Report, organizational document, July 1993.

- ↑ American Legislative Exchange Council, 1998 ALEC Annual Meeting brochure, organizational document, August 18-22, 1998.

- ↑ American Legislative Exchange Council, ALEC MODEL LEGISLATION, organizational website, archived by the WayBack Machine February 9, 1998, accessed October 2013.

- ↑ Center for Responsive Politics, ORGANIZATION PROFILES: Waste Management Inc.: All Cycles, OpenSecrets federal political influence database, accessed August 2015.

- ↑ Center for Responsive Politics, Lobbying: Waste Management Inc (Issues), OpenSecrets federal lobbying database, accessed August 2013.

- ↑ Bracewell & Giuliani, LLP, Lobbying Report for client Waste Management, federal lobbying report, January 1 - March 31, 2013.

- ↑ Bracewell & Giuliani LLP, Lobbying Report for client Waste Management, federal lobbying report, April 1 - June 30, 2013.

- ↑ Center for Responsive Politics, Waste Management Inc, spending profile, accessed August 2015.

- ↑ Center for Responsive Politics, PACs: Waste Management Inc Summary, OpenSecrets federal election contribution database, accessed August 2013.

- ↑ National Institute on Money in State Politics, Noteworthy Contributor Summary: Waste Management, Follow the Money state lobbying database, accessed August 2013.

- ↑ National Institute on Money in State Politics, Client Summary: Waste Management, Follow The Money state political influence database, accessed September 2013.

- ↑ Good Jobs First, Waste Management (total calculated by Center for Media and Democracy from downloaded CSV file), Subsidy Tracker database, accessed July 22, 2014.

- ↑ Waste Management, DEF 14A proxy statement SEC filing, March 30, 2011.

- ↑ American Institute of CPAs, "Fraud at Waste Management" (2005), Slide 4, accessed November 6, 2013; see also, Julie Creswell, "Scandal Hits -- Now What? Before Enron There Was Waste Management. Here’s How It Came Back from the Brink," CNNMoney, July 7, 2003.

- ↑ Robert Manor, "Garbage Hauler Settles SEC Suit," Chicago Tribune, August 27, 2005.

- ↑ Molly Ryan, "Face to Face with David Steiner," Houston Business Journal, April 6, 2012.

- ↑ Waste Management, "David P. Steiner: President and Chief Executive Officer," accessed November 6, 2013.

- ↑ Duncan Martell, "Gates Investment Arm Trashes Waste Management Bid," Reuters, August 1, 2008.

- ↑ Melinda Peer, "Waste Management Ends Republic Siege," Forbes, October 13, 2008.

- ↑ Dan Fost, "Garbage Firm Has History of Playing Tough," SFGate, July 19, 2007.

- ↑ Sewell Chan, "Trash Workers Go on Strike After Months of Negotiations," New York Times, April 4, 2006.

- ↑ Sewell Chan, "As Tension Grows, So Does Scrutiny of Long Strike by Trash Workers," New York Times, July 8, 2006.

- ↑ Marcus Moore, "Waste Management Workers on Strike," The Gazette (Maryland), April 7, 2006.

- ↑ Alex Dobuzinskis, "Waste Management Making Permanent Hires to Replace Striking Workers," Los Angeles Daily News, October 26, 2007.

- ↑ Teamsters Local 200, "Milwaukee Teamsters Call On Waste Management to Stop Threatening Workers" (press release), WisBusiness.com, August 26, 2008.

- ↑ Nancy Bartley, "Waste Company Brings in Replacement Workers," Seattle Times, July 26, 2012.

- ↑ Teamsters, "Drivers, Mechanics, Helpers, Yard Crew Seek Respect, Fairness on the Job," labor union press release, March 1, 2013.

- ↑ International Longshore and Warehouse Union, "ILWU Workers Strike Against Waste Management’s Unlawful Behavior," labor union press release, April 2, 2013.

- ↑ Claudia H. Deutsch, "A Garbage Hauler Tidies Up Its Image," New York Times, February 7, 2008.

- ↑ Waste Management, SEC DEF 14A proxy statements, 2006-2012.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 65.3 65.4 65.5 65.6 65.7 Waste Management, "2014 Proxy Statement," SEC filing, March 26, 2015.

- ↑ TE Connectivity, DEF 14A proxy statement," SEC filing, January 11, 2013, p. 57.

- ↑ FedEx Corporation, DEF 14A proxy statement, SEC filing, August 12, 2013, p. 65.

- ↑ Waste Management, Leadership, corporate website, accessed July 22, 2014.

- ↑ Waste Management, Board of Directors, corporate website, accessed July 22, 2014.